Defect Hunting

When designing Lockbook we knew we wanted to support a great offline experience. To our surprise, this grew to become one of the largest areas of complexity. Forming consensus is an active area of research in computer science, but Lockbook has an additional constraint. Unlike our competition, large areas of complexity take place on our user’s devices that can't update remotely. Additionally, the administrative action we can take is limited: most data entered by users is encrypted, and their devices will reject changes that aren’t signed by people they trust. All this is to say that the cost of error is higher for our team and it’ll likely take longer for our software to mature and reach stability. Today I’d like to share a tester we created to help us find defects and accelerate the maturation process. We affectionately called this tester “the fuzzer”. We’ll explore whether this is a good name a bit later, but first, let’s talk about the sorts of problems we’re trying to detect.

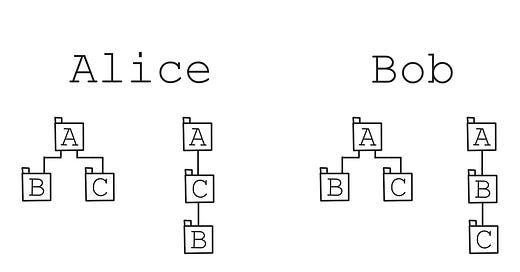

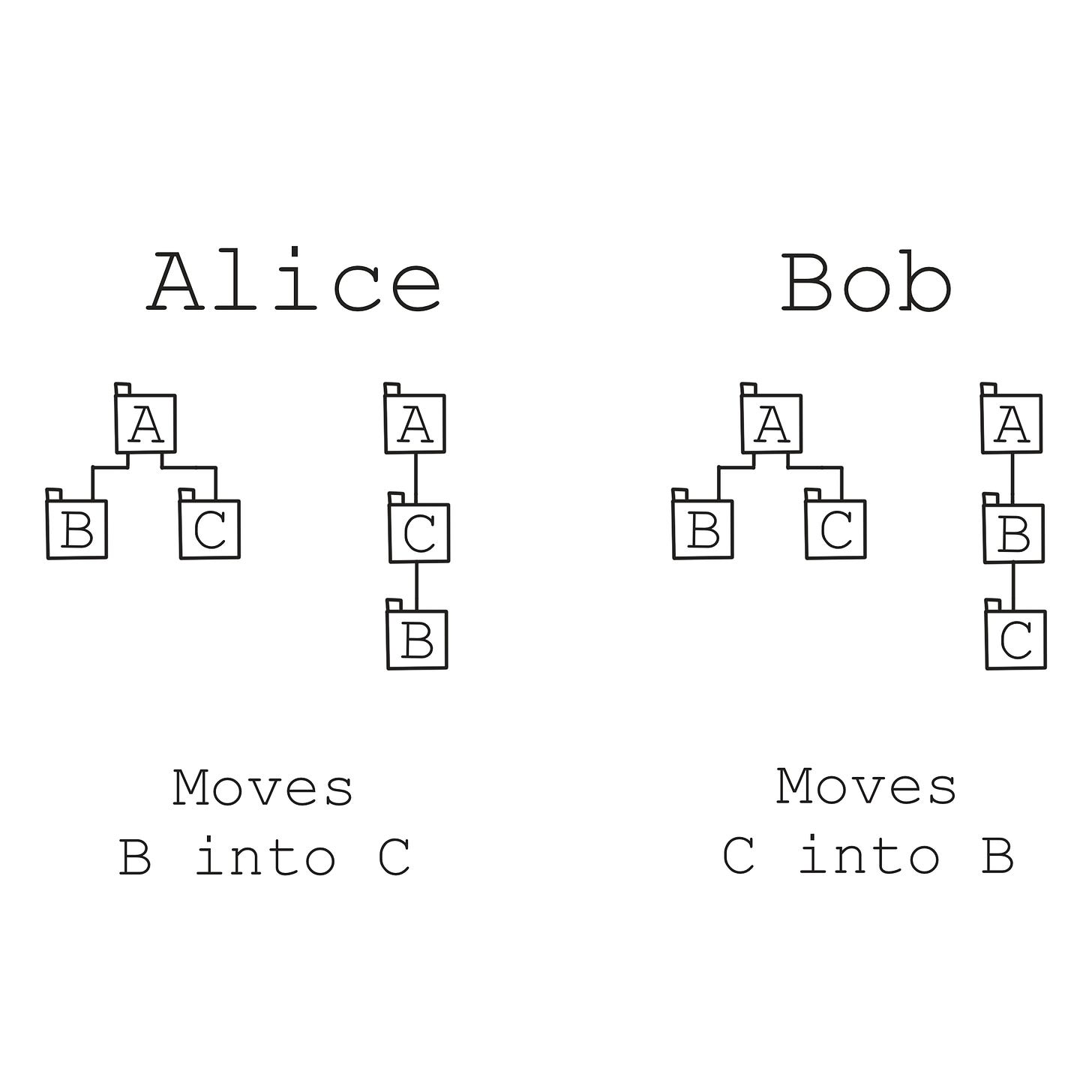

Users should be able to do mostly anything offline, so what happens if, say Alice moves a document and Bob renames that document while they were both offline? What happens if they both move a folder? Both edit the same document? What if that document isn’t plain text? What if Alice moves folder B into C, and Bob moves folder C into B at the same time?

Some of these things can be resolved seamlessly while others may require user intervention. Some of the resolution strategies are complicated and error-prone. The fuzzer ensures regardless of what steps a user (or their device) takes various components of our architecture always remain in a sensible state. Let me share some examples:

Regardless of who moved what files and when, we want to make sure that your file trees never have any cycles.

No folder should have two files with the same name. Creating files, renaming files, and moving files could cause two files in a given location to share a name.

Actions that change a file's path or sharees could change how our cryptography algorithms search for a file's decryption key, we want to make sure for the total domain of actions your files are always decryptable by you.

As we used our platform we've collected many such validations that we want to ensure never occur for the global set of actions on our platform, and the fuzzer's job is to spit out test cases that violate these constraints. It does this by enumerating all the (significant) actions a user can take on the platform across N devices and with M collaborators. It randomly selects from this space and at each step it asks all parts of our system to make sure everything is still as it should be. It does this process in parallel fully utilizing a given machine's parallel computational resources. It travels through the search space in a manner that limits the amount of recomputation of known good states, fully utilizing a given machine's memory.

Generally when people say they're fuzzing, they mean handing a user input (like a form field) randomized input to try to produce a failure. Our fuzzer captures that spirit of this but is different enough that plenty of people have raised an eyebrow when I told them we call this process fuzzing. Unfortunately, Test Simulator isn't as cool a name. Knowing what this process is now if you can think of a cool name, do tell us.

Today our highly optimized fuzzer executes close to 10,000 of these trials per second, however initially it was just a quick experiment I threw together to gain confidence in an early version of sync. This was written when we were still using an architecture that used docker-compose to spin up nginx, postgres, and pgbouncer locally. The fuzzer almost immediately found some bugs. We fixed these bugs, and the value of the fuzzer was made apparent to us. The time between defects started to grow and so did the intricacies of the bugs the fuzzer revealed. As a background task, we continued to invest in the implementation of the fuzzer, and the hardware it ran on. As our architecture became faster, so did the fuzzer alongside it. Today the fuzzer has been running continuously for months and has verified 10s of billions of user actions, a promising sign as we get ready to begin marketing our product.

Below are some of the fuzzer's key milestones. If you're interested in browsing the most recent implementation you can find it linked here.

15 Trials Per Second

Initially, we were running the fuzzer on our development machines, kicking it off overnight after any large change. Our first big jump in performance came from deciding to run it on a dedicated machine and trying to fully utilize that machine's computational resources.

80 Trials Per Second

We first tried running our fuzzer on a dedicated server which had 80 vcpus. We purchased this machine for $600 in 2020. Most of our early optimization efforts centered around tuning Postgres to perform better.

250 Trials Per Second

Our next largest jump in performance was when we made the switch from Postgres to Redis, and upgraded the hardware that the fuzzer runs on. After 2 years of faithful service, our Poweredge experienced a hardware failure which we weren't motivated enough to diagnose. So in 2022 we pooled our resources for a 3990X Threadripper with 120 vCPUs.

900 Trials Per Second

Before db-rs there was hmdb which was similar in values to db-rs, but worse in execution. It still served our needs better than Redis and performed better as it was embedded in the process rather than something that communicated over the network. It additionally used a vastly more performant serialization protocol across the whole stack, inside [core] and our server.

4000 Trials Per Second

In late 2022 I created a compile-time flag in [core] which allowed us to directly compile the entire server into core during test mode. This meant that instead of executing network calls for fetching documents and updates core was directly calling the corresponding server functions. At this point, no part of our test harness was using the network stack.

10,000 Trials per second

Once db-rs was fully integrated into core and server, I added a feature to db-rs called no-io, which allowed core and server to enter a "volatile" mode for testing. This also allowed instances of core, server, and their corresponding databases to be deep copied. So when a trial ran, if most of the trial had been executed by another worker, it would deep copy that trial's state and pick up where it left off.

Future of the fuzzer

Personally, the fuzzer has been one of the most interesting pieces of software I've worked on. If, like me, this piques your interest and you're interested in researching ways to make it faster with us, join our discord.